What is harder than learning? Unlearning

This image from Roger von Oech's “A whack on the side of the head” 1983 has intrigued me for years. The idea that we get rid of ideas or concepts is thought-provoking.

How do we know when to reject ideas?

What is the thought process we use to unlearn something?

My understanding of learning new ideas is clear and well-developed. During the time while I was pursuing my second graduate degree, I experienced an epiphany. I learned how to learn. I am proud of my skills and abilities to learn new things.

My understanding of the process of unlearning is less clear.

How does unlearning occur?

Unlearning is the process of abandoning or giving up knowledge, values, or behavior either unconsciously or deliberately (Coombs et al, 2013).

Why is it important to unlearn?

Healthcare is an evolving constantly changing field. What was known in the past can be proven wrong. Where would we be if we did not unlearn the treatment of bloodletting to treat infection? Where would we be if we did not unlearn that stomach ulcers were not a result of stress and eating spicy foods, but of H.Pylori bacteria?

Studies have shown that from 16% to 40% of highly cited and accepted medical research is later contradicted.

According to J Braithwaite and colleagues, 60% of healthcare is in line with the best available evidence, 30% is a waste or low value, and 10% is harmful.

Many things we know in healthcare are incomplete, dangerously flawed, or simply incorrect.

Mistakes require unlearning.

Unlearning as a process can bring to the surface things, we take for granted like biases.

Why is unlearning so overlooked?

There are many reasons unlearning is a neglected topic.

To meet patients’ expectations for quick concrete answers often healthcare providers default to heuristic thinking. Heuristics are mental “shortcuts” in clinical decision-making. Rule of thumb thinking provides quick simplified advice based on basic rules of a particular subject or course of action. Heuristics is mostly positive facilitating efficient healthcare but limits critical thinking and unlearning.

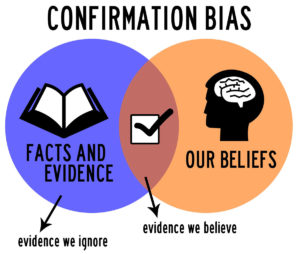

We have confirmation bias, which tends to cherry-pick, recall, and interpret information to confirm our existing ideas, views, and values. Being presented with facts suggesting our current beliefs are wrong is threatening. It is difficult to change confirmation bias.

It is easier to stay with old familiar habits and ideas. It is easier to introduce something new than to take out something old. New ideas and concepts are new and can be scary.

What do we know about unlearning?

The process of unlearning is a neglected topic and an under-researched field, according to Donald Hislop & colleagues 2013.

In a PubMed search using the keyword “learning,” there are over 900,00 citations. Using the keyword “unlearning there are just 700 citations.

According to R Rushmer 2004, there are 3 types of unlearning:

- Fading/forgetting occurs through lack of use.

- “Wiping direct unlearning” requires conscious deliberate active actions by an individual to change the way they think and act.

- Deep unlearning: shock and rupture occur when one’s mental model is incorrect, revealing a gap between reality and what we believe about the world.

I have forgotten and lost the ability to write in cursive, through lack of use.

There are times when I recognize that I have forgotten something that I had learned before. Sometimes my automatic response is wow, I have forgotten more than a beginner knows. This self-justifying egocentric response I often follow with a self-deprecating laugh.

An example of wiping direct unlearning is my beliefs about muscular trigger points and stretching exercises.

Over an extended period, I have come to not believe in the diagnosis of myofascial trigger points. Adam Meakins (2015) and Paul Ingram provide a good summary of the evidence that changed what I learned about myofascial trigger points.

Rushmer describes the type of learning of “deep unlearning: shock and rupture” as less deliberate, planned unlearning, but a sudden radical change. We unlearn from our mistakes which can be tragic events. My example of deep unlearning occurred from a mistake. The primary care physician referred a patient to me for left-sided neck pain. He was a middle-aged, active runner. My working diagnosis was a myofascial trigger point in the left upper trapezius neck muscle. I worked with him for several weeks providing massage, stretching excises, and changes in activities. Subsequently, I observed his obituary in the newspaper. He died of a cardiac event.

To complete the process of unlearning the last step is relearning.

The dramatic mistake of not considering the heart muscle as a source of this patient’s left-side neck pain I learned several things. I learned the importance of differential diagnosis. Consider the alternative. I learned when I cannot demonstrate progress to myself and the patient to consider the problem is not in my scope of practice and consider referring the patient to another healthcare provider for assistance. I learned that reading obituaries is a simple cheap continuing education process.

It is difficult to unlearn what we think we know.

How do we know what we know?

Learn, Unlearn, Relearn

“The illiterate of the 21st century are not those who can’t read or write but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn” Alvin Toffer

The information on this website is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. You are encouraged to perform additional research regarding any information contained available through this website with other sources and consult with your physician.

Damien Howell Physical Therapy – 804-647-9499 – Fax: 866-879-8591 At-Home, At Office, At Fitness Facility – I come to you, I do home visits Damien@damienhowellpt.com