Adjusting exercise load to optimize capacity performance

When it comes to adjusting exercise loads to optimize performance capacity it necessitates both art and science.

“Load management” in athletics and sports is a popular strategy to control the training volume, intensity, and rest to optimize performance while minimizing the risk of injury.

To improve performance or capacity, the exercise/load must exceed the individual’s current capacity, but not be so great that it results in tissue damage. ref

Managing or adjusting the capacity. Managing is to act skillfully or efficiently. Whereas adjusting is changing something to make it suitable for new use or situation.

Load management involves adjusting the amount of load to determine whether:

- It is too much.

- It is too soon.

- It is too little.

- The Individual is not ready, yet.

- The Individual is not prepared.

A bicycle tire needs enough air pressure to perform. If there is too much air pressure the bicycle tub explodes. There is not enough air pressure, the bicycle tube is not ready.

Measurement of load:

There are a variety of diverse ways to measure load (exercise; activity; stress; competition). It can be as simple as recording the distance you walked or the time exercising.

Better is to include a measure of intensity of exercise, either using heart rate or level of perceived exertion. Standardized Borg 14-point scale. Ref or Foster 10-point scale ref scale of perceived exertion while exercising is available.

Multiply the duration of the exercise session by the rating of perceived exertion for the exercise session to calculate the “arbitrary unit” of training load. ref

There are a variety of wearable devices that can measure, record, and even calculate the exercise load.

Analysis of measurement of exercise load:

A common practice or tool in load management for sports is to use the ratio of recent training level relative to long-standing training level. It is the acute-to-chronic work ratio (ACWR). Monitoring the ACWR ratio may optimize performance and reduce the risk of injury.

To calculate the ACWR ratio, divide the recent load by the long-standing load.

- Recent load ÷ long-standing load = ACWR ratio.

Example A:

An example using the activity of step count.

- The average number of steps for the recent week is 7,7000 steps/day.

- The average number of steps/days for the previous 4 weeks is 7700 steps/day.

- 7,700 steps/day ÷ 7000 steps/day = ACWR of 1.1

- Some of the newer wearable devices will provide this calculation.

Example B:

- The average number of steps/days for the recent week is 12,00 steps/day.

- The average number of steps per day for the previous 4 weeks is 7,000 steps/day.

- 12,000 steps/day ÷ 7000 steps/day = ACWR of 1.7

Example C:

Another example is using the level of perceived exertion times the duration of an exercise session.

- The athlete self-reports the exercise session is “somewhat hard” 4 out of ten.

- It is a 55-minute exercise session.

- Level 4 level of exertion x 55 minutes = 220 arbitrary units.

- The average number of arbitrary units per day for the recent week is 230.

- The average number of arbitrary units per day for the previous 4 weeks is 220.

- 230 arbitrary units recent ÷ 220 arbitrary units previous 4 weeks = ACWR of 1.0

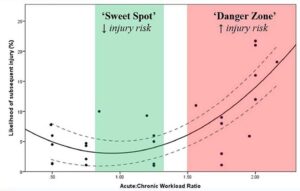

Interpretation of ACWR ratio:

- A ratio of 1.0 indicates the individual is well-prepared state.

- A ratio greater than 1.2 indicates an increased risk of injury.

- A ratio of 1.5 indicates a significantly greater risk of injury.

- A ratio of less than 1.0 indicates the risk of decreasing capacity.

The image graph is from Gabett, Tim - 2015

For Example, A the individual is in the sweet spot.

For example, B the individual is at risk of injury.

For example, in C the individual is in the sweet spot.

10% rule:

A common belief is the 10% rule, to avoid injury in training you should never increase the load by more than 10% each week. The supposed sweet spot using the ACWR ratio is 0.8 and 1.3. A ratio of 1.3 is equivalent to a 30% increase. Tim Gabbett review of the literature concludes the 10% rule is more myth than science.

The 10% rule is likely too cautious for healthy athletes.

Future Questions:

The system described above is for healthy athletes.

For individuals with musculoskeletal pain syndromes, what are the considerations and modifications to the process?

Stay tuned for next month’s blog post.

The information on this website is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. You are encouraged to perform additional research regarding any information contained available through this website with other sources and consult with your physician.

Damien Howell Physical Therapy – 804-647-9499 – Fax: 866-879-8591 At-Home, At Office, At Fitness Facility – I come to you, I do home visits Damien@damienhowellpt.com