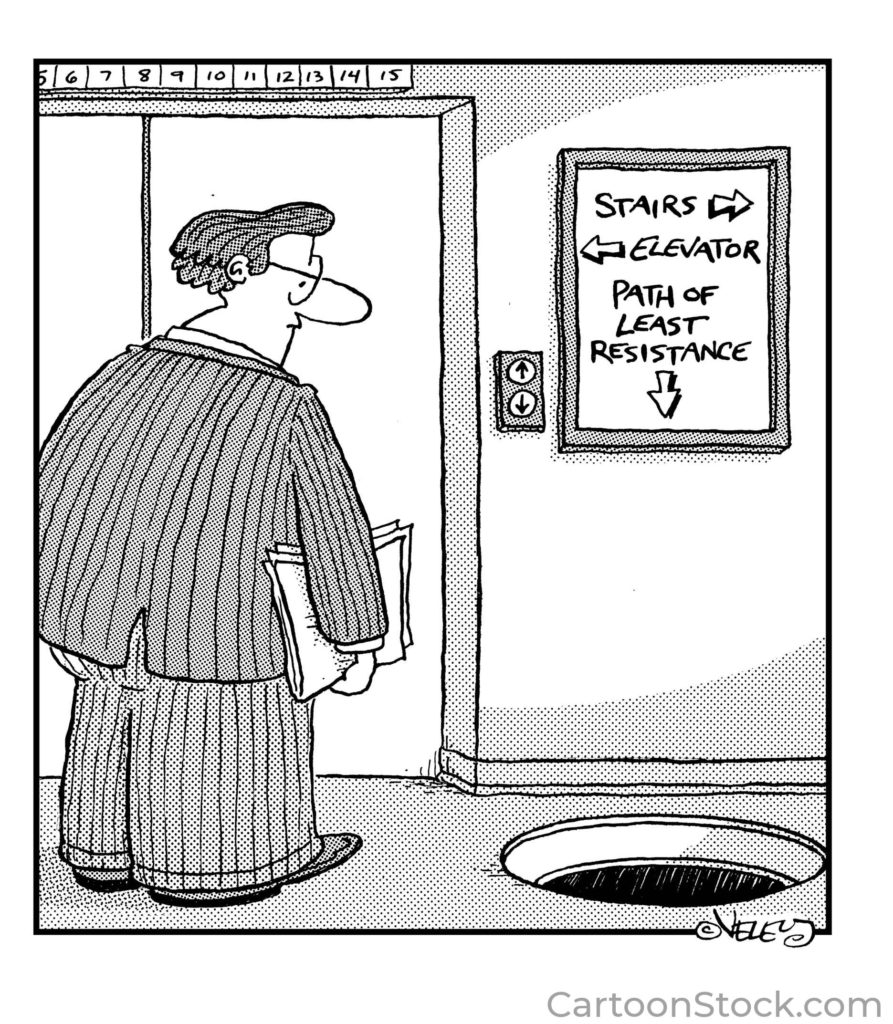

Path of least resistance is not always the best option – sometimes it is better to have some stiffness

There are three possible relationships between movement and musculoskeletal pain syndromes. There is either too much movement, not enough movement, or an optimal amount of movement.

When a muscle tendon unit and/or joint is flexible, hypermobile, or unstable there is too much movement.

When a muscle tendon unit and/or joint is stiff or hypomobile there is too little movement.

The relationship or proportion of too much movement – flexibility and too little movement – stiffness is critical to understanding musculoskeletal pain syndromes. This relationship is “relative flexibility/stiffness.”

The relative flexibility/stiffness determinant is the physical metaphorical explanation of the “path of least resistance.” The path of least resistance explains which muscle-tendon unit or joint is moving too much. The path of least resistance is determined by the relative flexibility and the relative stiffness of adjacent body parts.

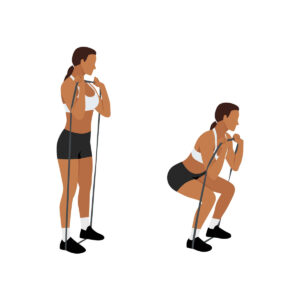

In the image below if the elastic band on the right side of the body is stiff, and less flexible, and the elastic band on the left side is flexible and less stiff then the squat movement will be asymmetrical. She will likely tilt lean to the right and the left side of the body will move more.

Dr. Jared Vagy provides a good YouTube video demonstrating this concept.

Increased stiffness of one muscle group or joint can lead to compensatory increased movement at an adjacent muscle group or joints that are less stiff.

The bigger thicker a muscle is the stiffer it is. Having increased stiffness or resistance to change can be a good thing.

Performing a golf club swing requires rotation thoracic spine, lumbar spine, hips, knees, and feet. The rotation motion should occur primarily through the thoracic spine and hips. If the thoracic spine and hip joint are relatively stiff and less mobile, the adjacent lumbar spine and knees may compensate and move too much or become more flexible resulting in either low back pain or knee pain.

Subjecting tissues to greater amounts of movement are susceptible to pain syndromes.

What moves too much is usually what hurts rather than what moves too little.

Andre Marich and colleagues comparing individuals with back pain to individuals with no back pain found individuals with back pain displaying more movement and greater excursion of motion early in functional movements compared to individuals without back pain.

Question: Given that musculoskeletal pain syndromes can have both too much movement and too little movement co-occurring or there is a disproportion of the relative flexibility/stiffness the questions that evolve are:

- How to decrease stiffness – increase flexibility

- How to increase stiffness – decrease flexibility

- Which question should be addressed first?

Accepting or choosing the path of least resistance likely means there will be more movement or too much movement – not enough stiffness and too much flexibility.

Therefore, interventions to increase stiffness, and decrease flexibility is a logical first approach.

Potential interventions to increase stiffness can include:

- Isometric strengthening exercise, and here, and here, and here, and here, and here, and here

- Strengthening exercises at end range of motion

- External supports, braces, strapping

- Conscious alteration of habitual alignment and movements

- Functional movement pattern training identifying the movement, that is occurring too much, the direction of movement, and with a conscious effort to alter this excessive movement.

Choosing the path of least resistance is not always the best option.

Muscles are rarely too short or too stiff. If they are it is likely because the adjacent muscle/joint is too flexible. If stretching exercises are not working, consider the alternative.

- That’s a stretch: why stretching may not always be the solution.

- Should you stretch it out – Pain too loose too stiff?

- Pain on the bottom of the heel: Too much big toe motion.

Stiffness is more often the result of too much movement and not the cause of the pain. If it feels stiff, then look for adjacent tissue or joint which is too flexible.

Rather than immediately seeking a stretching exercise to alleviate pain, take a moment for critical thinking. Choose the more challenging path.

Signpost on top of the mountain warning challenges ahead and three options

- Which movement(s) provoke the pain?

- What is the direction of movement provoking the pain?

- Is there too much movement or not enough movement?

- How can I alter the painful movement to limit the direction and/or magnitude of movement?

- Which should I address first intervene to increase stiffness or intervene to become more flexible?

The information on this website is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. You are encouraged to perform additional research regarding any information contained available through this website with other sources and consult with your physician.

Damien Howell Physical Therapy – 804-647-9499 – Fax: 866-879-8591 At-Home, At Office, At Fitness Facility – I come to you, I do home visits Damien@damienhowellpt.com